Pictures: Joseba Aguirre

When describing the manner in which custom bikes are crafted, us eloquent wordsmiffs, like, are wont to use some fairly flowery language so as not keep repeating words like ‘built’, ‘made’, ‘welded up’ et cetera, et cetera.

Enjoy more Back Street Heros reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

One of the most apt of these terms wot we use to describe the bending, shaping and working of metal is ‘sculpted’. Yes, I know that in its strictest sense it means ‘to create or represent (something) by carving, casting, or other shaping techniques’, and most folk, on hearing the word ‘sculpted’, will imagine Michelangelo (no, not the green-shelled geezer with the orange mask and the nunchucks) with his chisel banging out huge marble sculptures of Biblical heroes without their pants on or Henry Moore’s cast bronzes of the kind of figure that most of us only see when we’ve accidentally eaten a little too much of a particularly psychoactive fungus that grows on Welsh hillsides, but actually ‘sculpted’ is a good word for describing hand-built custom motorcycles, especially ones that are as organic-looking as the one you see here in front of you.

Built by a gentleman by the name of Alexis Domeneq, born in Havana in Cuba, but now resident in Barcelona in Spain, it started life as a humble Yamaha XJ600 of 1989 vintage, although you’d be forgiven for not realising that immediately. Growing up he studied chemistry and worked for a while as a specialist chemist, separating out gold and silver from mines, but that was never really his passion. No, from early childhood he spent a lot of time at his uncle’s carpentry workshop, learning to shape and carve wood, followed by a time helping a local luthier (an artisan who builds or repairs stringed instruments generally consisting of a neck and a sound box – the word “luthier” comes from the French word luth, which means lute), and at just 22 years old he made his first concert guitar (he’s also a very talented guitarist). From there he moved on to learning to paint, and restore paintings, with noted Cuban artist Pedro Amador, and then to working as a sculptor for the Office of the City Historian in Havana, helping to turn Communist Old Havana into a thriving modern metropolis, yet retain its original character. And, as well as that, when he did have any spare time (when?!?) he restored classic bikes, modifying and adapting them ‘Cuban-style’ (which, because of the now famous US embargo on all goods except food and medical supplies to Cuba that started in 1960, means fixing them with whatever was at hand). Then, in 1997, he moved to Barcelona where he worked in that city’s most famous landmark, Antoni Gaudí’s legendarily unfinished church La Sagrada Familia, sculpting the birth façade, and ever since he’s been working as a sculptor in Barcelona.

He’s never been far away from bikes though, and sees them as perfect blank canvases to express ideas with as bikes move around and so more people can get the chance to see them than they perhaps would a static artwork. A friend was about to throw a very old and knackered XJ600, and Alexis asked if he could have the bike to work with, and his friend agreed. So began a build, his very first, with a very low budget and, he says, not as much time as he’d’ve liked to spend on it.

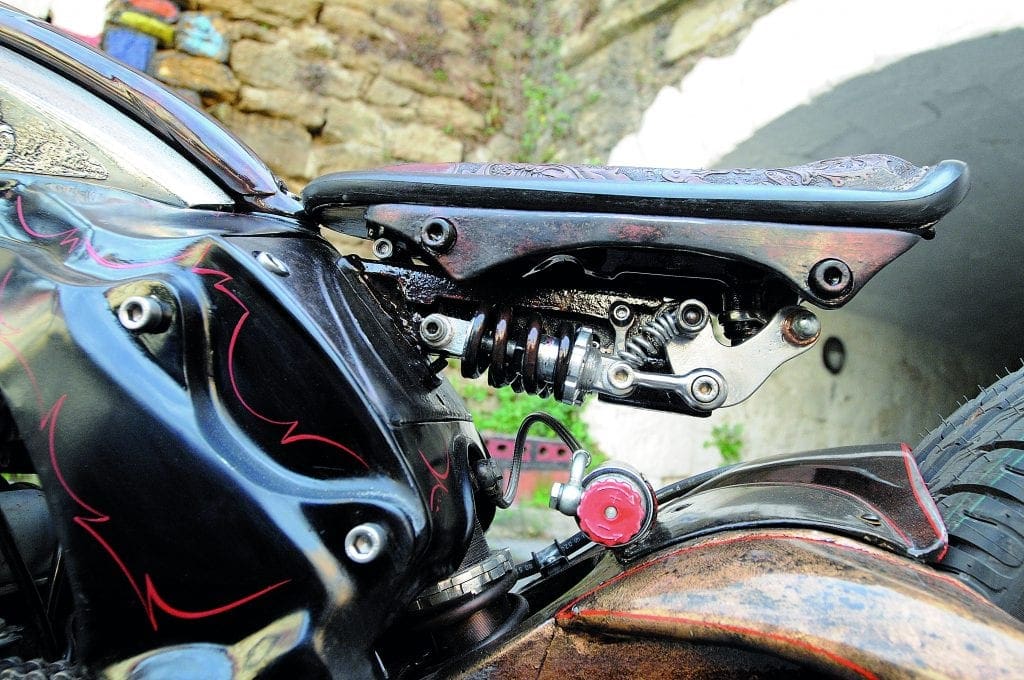

The first thing he did was to cut the bike into pieces and throw away most of it. He wanted the bike to be long to represent the road, the trip; low for his own origins that he didn’t want to forget; and to conform to the ancient Greek idea of the golden ratio – a fantastically complex mathematical idea that’s been used by everyone from ancient Greek polymaths Pythagoras and Euclid to modernist architect Le Corbusier and out-and-out oddball Salvador Dali. As I only got a CSE in Maffs, I won’t try and explain it, but it’s all to do with the symmetry of proportion, okay? Using these ideas he remade the frame, raking the front to sit low, and created the one-off front suspension arrangement. He then handmade the fuel tank and engraved it, taking inspiration from Old Masters like Durer, Celini, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Goya, and reworked an Aprilia RS250 swingarm to take a wider wheel from a car.

The seat was made to be as soft and comfortable as it could be because the reworked Showa shock has so little travel, and the embossed leather on it is an interpretation of a Dürer engraving.

The headlights are home-made too, and are directionally adjustable, and he handcrafted the very art-punk touches throughout the bike too, like the levers, the fuel cap, the ’bars and… well, just about everything else too, using just a disc cutter, an English wheel, a big hammer and a TiG welder – no CAD, no big machines, nothing.

Alexis says he probably made enough pieces while creating this bike to have made another one at the same time, but he’s only used the very best parts on it.

He’s a quiet guy, but a true artist type – he describes the way he works as “sometimes chaotic, but always careful”, and says that “every piece I like is inspired by a mix of dreams, antiquity and modernity”. This, though, is true art – not a manky bed in a gallery, a tent covered in marker pen, or half a shark in a fish tank…