Here’s a fictional treat from the pen of Jim Fogg that was first aired when BSH was a newborn publication, but it still packs a powerful punch. Illustrations by Louise Limb.

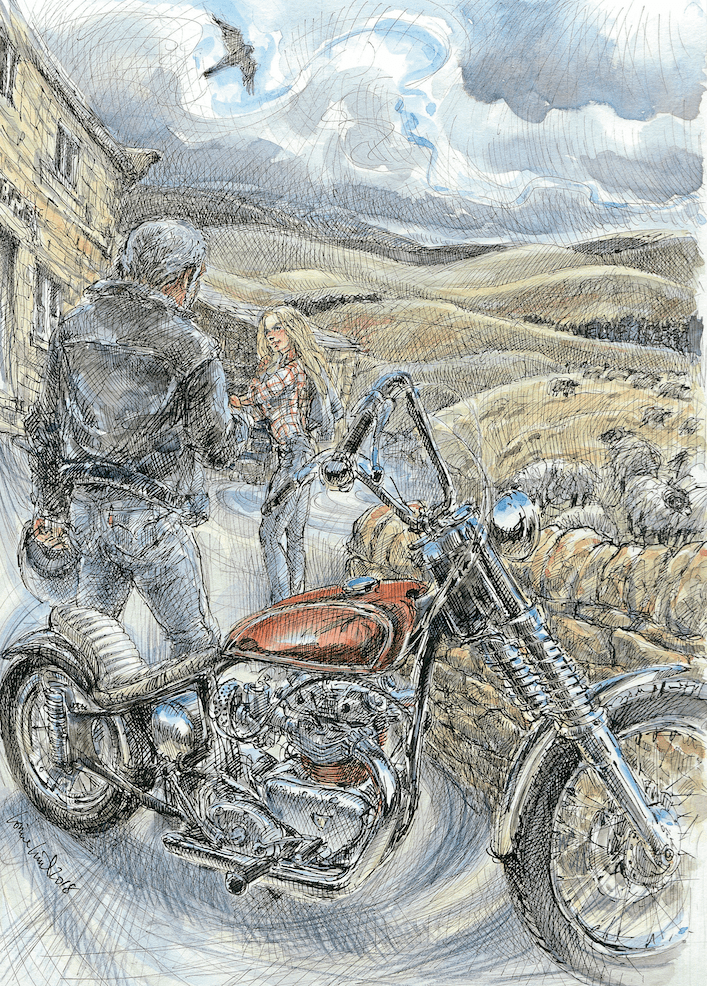

It’d been 18, maybe 19 years, since I’d ridden the high border country, and I’d almost forgotten how bare and cold it was on those narrow moorland roads, even in summer. The wind moans across the fells, which are higher than most rocky outcrops we call mountains in England, and it tears at the tussocky grass, and swirls the shaggy, dirty fleeces of the black-faced sheep. The roads are like black ribbons, unwinding across a landscape unchanged mostly since men moved slowly northward thousands of years ago, following the retreating glaciers. It’s a mad, bad place to ride, and it always appeals to any biker old enough to have a little of the stark craziness of winter in his soul, the icy lunacy of someone who knows the places to run to closed down a long time ago…

In the softer places of the downlands, and in the towns and cities, people will talk to you, and smile, and then stab you from behind; up on the high border country you meet a hard stare, and a distrust and a shake of the head that’s more understandable somehow. Don’t expect any friendliness from the Annstrongs, the Scotts, the Frasers or the Hewitsons – for hundreds of years they’ve lived in the Debatable Lands between Scotland and England, and’ve been raided by each other and stolen each other’s cattle and wives often enough to have become hard, taciturn people with little faith in outsiders. This much – this dislike of prying strangers, and a hatred of being told how to live by softer, more settled people – they share with bikers. But that’s as far as they go.

Enjoy more Back Street Heros reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

You’ll meet similar people all over the world, from the farmers of the Appalachians to the sheepherders of Queensland; polite, quiet people who are courteous and hospitable as long as you’re just passing through, but whose tempers, once roused, burn with a cold fierceness towards strangers who’ve angered or upset them – or who try to stay too long. But – I was thinking as I rode along, with the wind in my eyes and the deep and mellow exhaust-note trailing behind me along the road – 18 years or so is a long time…

Even so, it was surprising how little’d changed, as far as I was concerned. I was 50lb or so heavier, and my hair’d become greyer and shorter – just like my outlook on life – but I still wore faded Levis and the same black leather jacket, and I was still struggling to make a living, keep a girl, and make enough money to support the odd habit or two and a simple lifestyle that everyone else insisted on making more complicated. I smiled, even the bike was the same, although you’d hardly think so, to look at it. But fashions change, even among bikers, and yesterday’s cafe racer becomes today’s lowrider, a better choice for a middle-aged guy with a beer-gut and a stiff spine, maybe.

A 1959 Triumph Thunderbird was no great shakes as a cafe racer anyway, even if it looked the part with its alloy tank, rear-sets and clip-on bars; a nice, punchy iron motor, but no brakes worth speaking of, and not too much in the way of directional stability around bends either. I’d sold it to a friend of mine around ’69 or ’70 – I can’t remember the year, but I know he gave me £140 for it, which went towards a BSA Thunderbolt – and, over about four years, he made it into what it should’ve been logically all along. The motor – its cast iron Sperexed bright red to contrast with the polished alloy of the casings and the chrome of the pipes – had gone into an earlier Triumph plunger frame which’d been given a coat of nickel, and had had a 5.00 x 16 rim and tyre put in it. Shortened Norton forks’d gone up front, topped by cowhorn bars, and’d been joined by a slim red tank from a Matchless scrambler and a white Cobra seat, and a narrow 21-inch front wheel. It was smart, rideable, eye-catching, and not too excessive; it wouldn’t win any prizes, but the owner at that time hadn’t any wish to compete with anyone for anything, in any case.

I eventually bought it back from his wife, shortly after he’d taken off to Istanbul and parts east aboard a VW camper loaded to the racks with Swedish au pairs, acid-heads and religious weirdos. His wife was so pissed off by his departure that she asked me what he’d given me for it as a cafe racer, accepted that as the price for a rebuilt lowrider, and threw in his complete set of workshop tools as part of the bargain.

I was enjoying riding the bike in its new incarnation, steering it along the roads which wound through the barren uplands where cars were as rare as the kestrels you could sometimes see hovering motionless overhead in the washed-out summer sky; as the bike runs free, so your mind can run free too, as the miles get eaten up unconsciously under the turning wheels. I crested a hill, and a small figure waiting by a dirt track leading on to the main road came into view, looking lonely in the space of the moorland. Buses up there run once every blue moon, so I drew to a halt to see if the waiting girl wanted a lift to wherever she was going.

She was a tall girl, in her late teens I guessed, and blonde-haired and a little on the plump side – not fat, but well covered, although when she was older, and with her hair tied back and a few kids to look after she’d be heavier, like a German hausfrau. As I looked more closely, I could see a dusting of freckles across her nose and hazel eyes, and a wide and generous mouth; she was wearing jeans, a checked shirt – the sort you see girls wearing in musicals like ‘Oklahoma’ – and a Levi jacket. Not my type these days, as you get older you prefer them smaller, more exotic, and livelier, but it seemed only polite to stop and ask if she wanted a lift, even so. “Just as far as The Drover’s Arms,” she told me, “on the road to Rigg. It’s about 10 miles or so – do you know it?”

I nodded. “I know it,” I told her. “Okay, get aboard, huh?”

“I’ve no helmet,” she answered. “Will it be okay?”

I handed her mine; the likelihood of a passing panda car driven by an officious copper was slim, and I suddenly fancied feeling the air blowing through what remained of my greying hair. We set off, the Triumph cruised easily along the unfenced roads, scattering sheep back to the moors with its mellow exhaust boom, and as I felt her hands resting lightly on my hipbones, I started remembering once again…

Eighteen, maybe 19 years ago, I’d been working on a mink farm up near Rigg. It sounds bizarre, but mink farms were an easy way to make money in those days, and even though the owner of the farm paid me little enough, the money I got was all my own because he let me sleep in an old caravan close to the farmhouse. In the evenings I used to ride the short distance to the nearest pub, The Drover’s Arms, and pass the time drinking beer, playing darts, and trying to get to know the local girls better. It was difficult trying to get to know anyone better in that part of the world; the local guys of my age were closemouthed and suspicious that I was after their girls, the old men just nodded as I went in and then turned back to the bar, and what few girls went into the pub tended to alternate between embarrassed giggles and smartass remarks when I tried to be friendly with them. All except one, anyway…

Janet Hewitson was a tall, blonde girl too, just like the one riding behind me on the Triumph all those years later, and she was 16 when I first met her. She was a farmer’s daughter, which sounds like the beginning of a bad joke, but was a nice, easy-going girl, slow and gentle in her movements, with a matching smile and a nature to match her generous figure with its wide hips and beautifully balanced breasts. Virgins, I’ve found, are a rare commodity these days, and not one I’ve ever set great store by, but you’ve got to remember I was a lot younger and a lot less shop-soiled myself – when you’re 18 it’s a challenge, and any guy who’s 18, unless he’s marked out for the priesthood, chases spare tail like it’s going out of fashion, just for the hell of it.

And what you lack in experience you make up for in persistence, not to mention sheer enthusiasm. That’s how Janet and I ended up every night for a month or so in my caravan; the deed was done quite a few dozen times, and I’d like to think we both enjoyed what was enough of a new experience for both of us to be memorable.

At that age, in those permissive days anyway, you tended to dress up what’s basically just the urge to screw your brains out with all the trappings of romance and talk about true love, beautiful feelings, and running away together and spending a lifetime in idyllic happiness; it’s a pleasant illusion, but the awakening comes soon enough…

In my case it came one evening when I’d ridden halfway up the track to her farm, where I always used to meet her before we went for a drink and then back to my caravan. I always stopped halfway up the track because her family weren’t too delighted to see me and, in any case, I used to like watching her come walking down between the drystone walls towards me, the smile growing on her face as she got nearer. Not that night, though.

I waited, and looked up towards the farm, but there was no sign. You know how you get a prickly feeling between the shoulderblades when you first begin to sense that someone you can’t see is watching you? You turn round and there’s no one there? It’s more of a shock when you turn round and there is, take it from me. Particularly when they kick the shit out of you.

The Hewitson men, unlike their womenfolk, are hard, rangy bastards, with horse-teeth and big, knobby bones in their fists and their cheeks and foreheads. I saw one of Janet’s brothers with a face dabbled with blood as my hand split the thin skin over a bony cheek, but then another head split my eyebrow and, as I was trying to get the blood out of my eyes, her father Jocky’s right hand cracked on my short ribs and dropped me to my knees trying to fight the waves of nausea. I kicked out at a kneecap as I struggled to get back to my feet, but there were three Hewitsons and only one of me. Eventually I settled for curling up in a foetal position and hoped they wouldn’t kill me, although it sometimes seemed the easiest way out as the heavy farm-boots went in.

They didn’t speak much at all, until the old man realised that I’d had enough, and more than enough. One of his sons rolled me over, and propped me up with my back to a drystone wall;

I tried to look up at the three of them, but everything was streaked red, and I couldn’t even attempt to speak.

“Had enough?” one of the brothers said, pressing his fingers to his split cheek. “Had enough, bastard?” He grinned wolfishly, and stepped forward.

Jocky Hewitson restrained his son. “Leave it, Davie,” he said sharply. “And you,” he went on, talking directly to me, “you keep away from Janet, because if you don’t we’ll kill you, you piece o’ shit. Take warning, my mannie, any word you’ve been sniffing around her, and you’ll get buried so deep on the moor the crows’ll need a bulldozer to find you…”

“Best get out o’ Rigg,” the younger brother told me. “Out, and never come back…” He put a boot-sole to the Triumph’s alloy tank, and casually pushed it off its prop-stand, so that the bike toppled over on to the pebbly earth of the farm track.

I heard the headlamp-glass shatter, and metal scratching on the stones.

The Hewitsons stepped over me, skirted carefully past the fallen Thunderbird and walked away, up the winding track back to their farm. I got out of Rigg, just as the youngest Hewitson had advised me – I took £30 wages from the mink farm, a bike that cost me £36 to repair, and two broken ribs, a broken nose, a chipped front tooth and cut lips, and black and purple bruises all over my body and thighs. I think, maybe, that I might just have been lucky to get away so lightly…

As I was riding along all those years later, with the young girl’s thighs cushioning my arse, and her boobs pressing into my back, I thought about it, and how it would’ve been different now. The situation wouldn’t have arisen – I stopped taking everything seriously some time back when I stopped taking myself seriously, particularly true love and romance – but no one, I thought as I sat there behind the Triumph’s ’bars like an ageing grizzly, would find me so easy to work over nearly 20 years on. You learn a lot about yourself if you’ve ridden bikes for 20 years; a lot about pain and anger, and a sight more about the general meanness of the world and your own in particular. I’m not a fighter, no sort of hard man, but I wouldn’t step off the pavement into the gutter for anyone on God’s earth, however many there were, because I’m as good as the next man, and maybe better than most. Young bikers believe they’re immortal: old bikers know they’re not, but don’t give a shit anyway…

It’s a simple philosophy, but one you tend to work out from the saddles of a lot of bikes over many thousands of miles and a number of years. When you’ve no place to run to, the place to stay is where you are…

I was thinking that as The Drover’s Arms came into view; a long, low, barn-like building dating from the days when Scots drovers brought their small black Galloway steers over the border to fatten them and sell the sweet tasting, gamey beef to us English. It hadn’t changed at all, except the car park had been given a coat of tarmac instead of granite chippings I remembered.

The young girl got off the Thunderbird, and I cut the motor and kicked the prop-stand down.

“Meeting someone?” I asked, and the girl smiled back.

“He’ll be some time, yet,” she answered. “But I’m used to waiting…”

“Okay, have a drink with me in the meantime,” I said. “Make an old man happy, huh?”

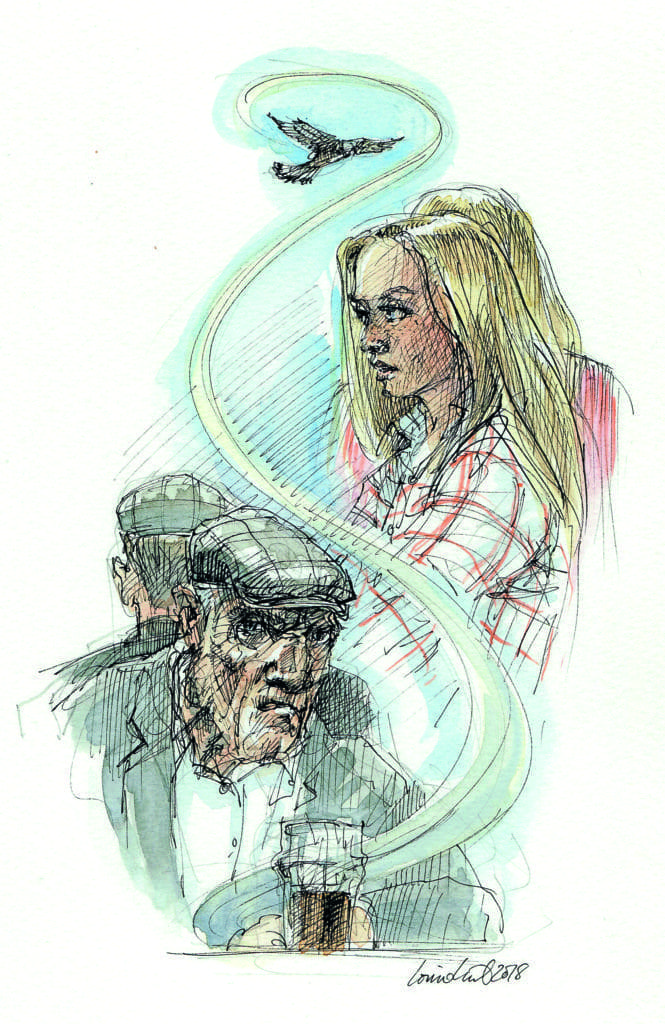

She nodded and grinned, and we went into the bar, dark-panelled and warmed by a smoky coal fire, with badgers’ and otters’ heads peering down dustily from wooden shields on the walls. I got the drinks, a pint of Cameron’s and a Britvic orange, and as I was waiting for my change from the old lady behind the mahogany bar, the only other customer, an old man in a blue suit and open-necked white shirt, wearing a tweed cap and heavy working boots, turned to make conversation with me. Or rather he turned to ask me my business, that’s how it goes in that part of the world. “Travelled far?” he asked, half turning to face me. “And where are you heading for then?”

As I saw him full-face, I realised it was Jocky Hewitson, Janet’s father. He was gaunter and much older somehow than I’d expected, but the tight bones in the face were still there, and I looked down at the bony knuckles of his big hands. There was something odd about him that I couldn’t place at first, and then I realised that one half, the left side, of his face was fixed and immobile, death-like, and that his speech was slower than I’d remembered and terribly slurred. He’d had a coronary some time back, a stroke, as they called it up there, and’d only just avoided dying.

“I’m passing through,” I told him, realising he hadn’t recognised me. “I’ve just dropped the girl over there down here – it was on my way, in any case…”

I nodded towards the girl sitting at a table.

He turned round to look at her, and the good half of his face purpled with sudden anger. She looked up, and her face drained of colour.

“So this is where you meet your bloody boyfriend,” the old man said, his voice louder and almost incoherent. “You come sneaking in here, you bitch, when you think none of us’ll be here. Well, I’ve got a surprise for you, girl – young Jocky and his mates’ll be here soon. And who’s this mannie here?” he asked, glaring madly at me. “More of your bloody bike trash friends?”

“I don’t know him,” the girl said, obviously terrified by old Hewitson’s anger. “He gave me a lift here – that’s all. I don’t know him, honest, Grandpa…”

Old and crippled as he was, I felt a rage stirring in me against the bloody-minded old bastard that Jocky Hewitson still was.

“She doesn’t know me,” I told him, “but I know you, Mr Hewitson…”

He looked closely at me, and there was a faint flicker of remembrance, the first stirrings of recollection. “Aye,” he mumbled, “aye, I mind you, too…”

The conversation was suddenly interrupted as someone else came into the pub. I hadn’t heard the bike, but the newcomer was a young, thin guy in leathers, and he was carrying two helmets – one his own, the other the young girl’s, I supposed.

Jocky Hewitson looked at the biker, and took a dragging step towards him. “You…you…” he slurred and stammered, unable to speak because of his insane loathing for the young guy.

The biker looked at him. “Eat shit, you worn-out old bastard,” he said, and turned to the girl. “Come on, then, Jenny, it’s a long way to Aldershot and I want to get married before I get posted again to Ulster…”

“Now might be as good a time to leave as any,” I said to them both, and told them what Jocky’d said about young Jocky and his mates arriving shortly.

“Bloody swede-bashers,” the young soldier said. “Maybe you’re right, though, Pops…”

I grinned; he was right – I was old enough to be his father.

I went out with them, and saw the happy couple ride off on a CB900 just as a battered pick-up was arriving in the car park from the direction I and the girl’d come. Three teenagers got out, all dressed in work-jeans, scuffed farm-boots and sweatshirts and truckers’ waistcoats.

“I think you’re too late,” I told them, and tried to keep the smile off my face. “They went thataway… and unless your Datsun’s got a turbo, I don’t think you’ll ever catch up with them…”

The three kids, one blond and thick-set, one thin with acne, and the last one tall and with a prominent Adam’s apple wobbling in a long throat, didn’t quite know how to take the middle-aged guy with the beer-belly and the beard straddling his Triumph, ready to ride off, but I knew how to take them… and I could’ve done it too, because they weren’t the same stuff as Jocky Hewitson and his sons’d been all those years ago.

Only one thing puzzled me – I still couldn’t work out which of the teenagers was young Jocky, because none of them bore much resemblance to the rest of the male side of the Hewitson family.

We stared at each other until a slurring voice broke into the meeting of eyes. Old Jocky Hewitson stood at the pub entrance and pointed at me with a shaking finger. “He’s one of them, Jocky lad,” he slobbered. “He’s the man who helped take our Jenny away, brought her for the soldier. Settle the bastard, lads…”

There was silence again, as the young men thought about their chances. The thick-set blond guy spoke. “Leave it alone, Granda,” he said, “we don’t want trouble…”

“Not with bloody outlaw bikers, any rate,” the thin one with acne muttered. “He won’t be alone, Mr Hewitson…”

“I’m sorry,” the young blond man said to me as I fired the Thunderbird into life. He shrugged, and gestured halfheartedly to old Jocky. “My Granda’s an old man, he gets upset easily, especially since he’s been ill…”

I used to make allowances for people, too, when I was young Jocky’s age… and before my hair went grey, it used to be that colour. “That’s okay, son,” I told him. “It’s not worth fussing over.”

He smiled nervously, relieved. “Aye, well,” he added, probably stuck for something to say, “it’s a sort of family matter, all this stuff with my Granda and my sister and her chap. You know how it is…”

“I know how it is, son,” I answered. “Take care, huh?”

I nodded to him and his mates, and looked across to where old Jocky Hewitson stood as if he’d been turned to stone, the dead side of his face unmoved by the cold moorland wind, his cold left hand clawed like a dead bird’s, the knuckles white as marble. A tear rolled from the right eye down the right cheek, but it might only’ve been dust from the moor being blown into his good eye… and whether it was the tear of an old man’s frustrated rage, or heartbreak for losing his granddaughter, didn’t matter to me at all. I was back in the breeze, with the Triumph’s exhaust-snarl wreathing down the road behind me, almost as tangible as my black scarf whipping into the wind, pointing back to the cold moorland pub and the three young men standing by the Datsun pick-up.

I settled down into the white Cobra seat and stretched my legs out to the highway pegs, watching the thin front tyre skate the white line, as I moved out centre to line up for the next sweeping bend on the black twisting road.

It’s a hard place, the high border country, particularly for people who’ve never learned to bend to the cold, harsh wind that’ll freeze you to the bone if you stay too long in it, and give you a heart like the rock that underlays the thin, poor moorland, cold like a stone…