Over the years I’ve learned not to put my lid on before I get the motor running, ’cos if my bike decides to be a bastard I can get pretty warm kicking and kicking, and I have, in the past, still been out of breath when I get to the cafe…

Words: John Evans

Pics: Simon Everett

Enjoy more Back Street Heros reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

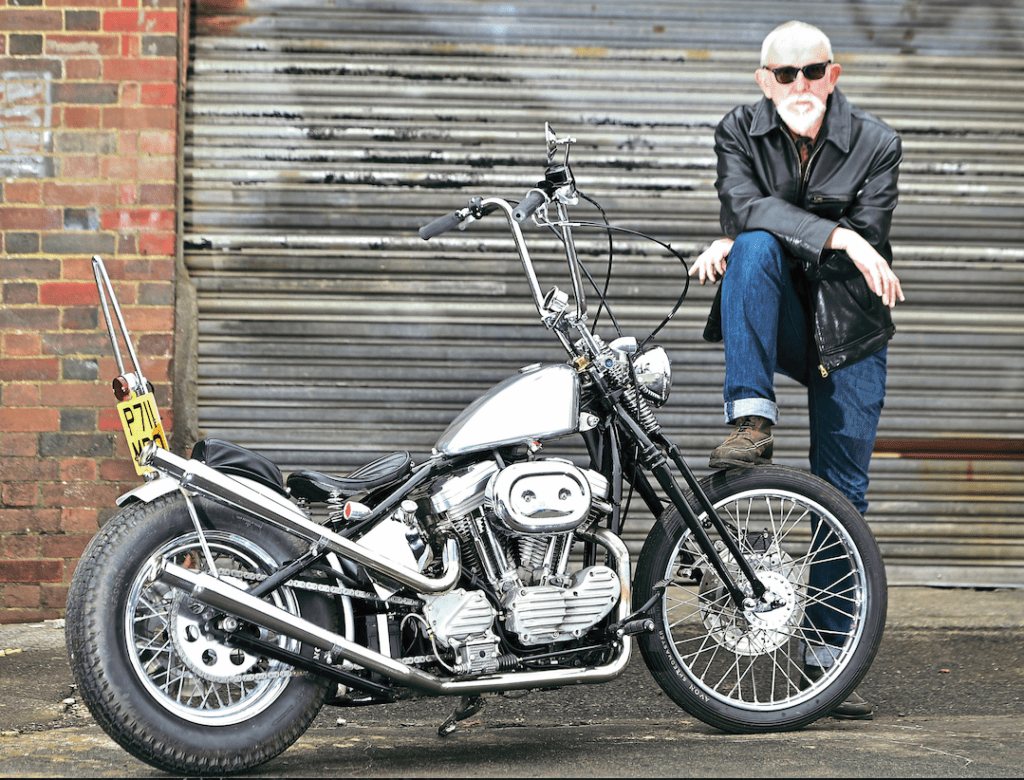

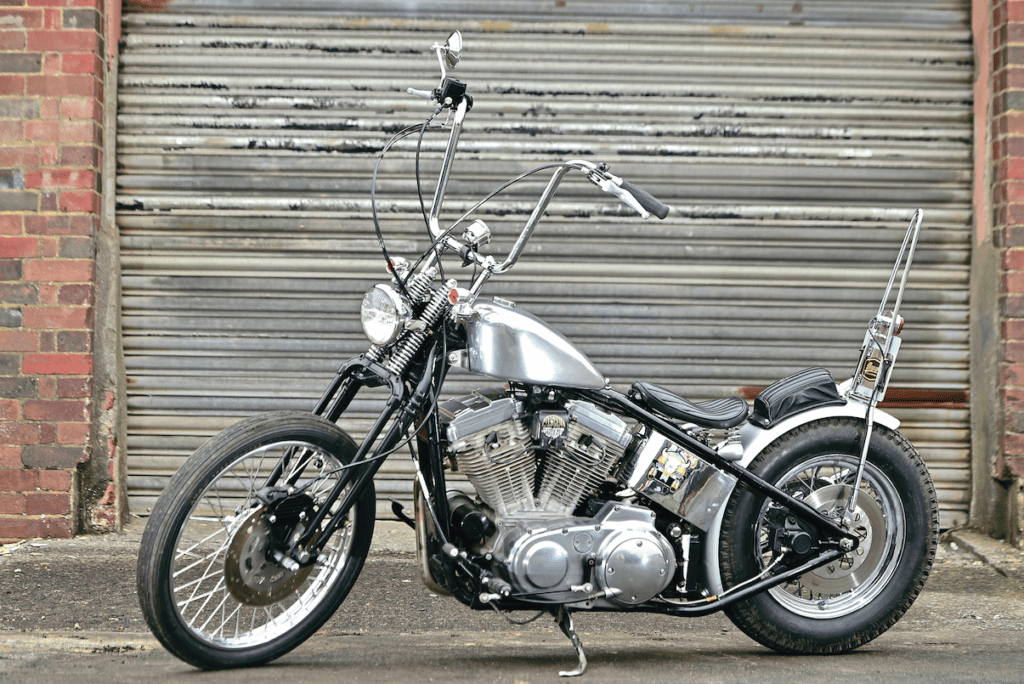

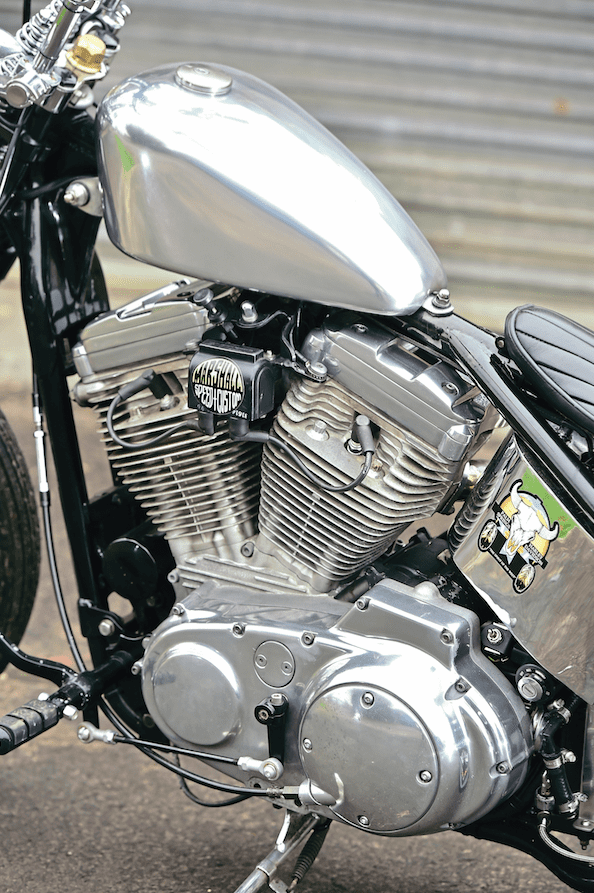

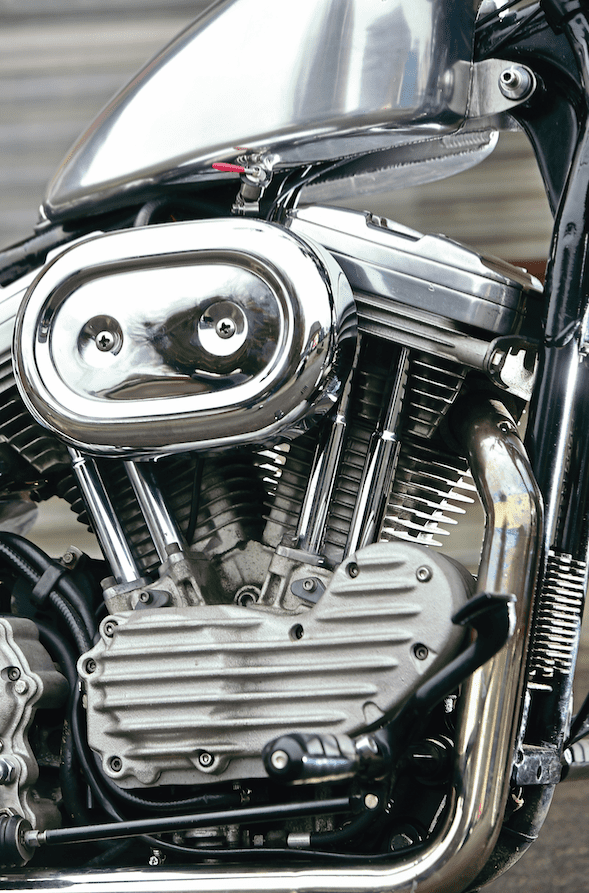

Modern bikes, ones with electric start and electronic ignition, are part of an easy life that I have been known to scoff at. I appreciate the authentic 1950s/60s experience. With all this in mind, my Sportster chopper concept was born. Why not? The 1200 V-twin is a really reliable power-plant and looks the biz, although I’m not that keen on the way the timing side looks, but putting that EMD cam cover on gives the 1997 lump a real 1950s vibe.

When the 1960s chopper builders needed a donor bike they didn’t start with an expensive classic bike – they used what they had that’d work. Even the Easy Rider bikes were from a scrapyard originally. Building an authentic ’60s chopper is an arm and a leg job (you knew that, right?) so I went with the spirit of the Sixties and used a relatively affordable Harley donor bike. I can tell you now, I’m lovin’ it!

The picture I had in my mind called for a very specific frame – no stretch or extra rake. This is where Owen James, hot rod builder, came in. He got it straight away, and set about chopping the original frame and fabbing a hardtail that looks as if it’d always been like that. He also constructed the horseshoe oil tank from a sheet of steel, and then set about making the stainless ’pipes; the crucial thing there being that the rear header starts curving as it comes out of the manifold, echoing the Paughco headers I had on my Panhead. He also supplied the tank – he didn’t want to part with the alloy fuel tank and we were only trying it on the frame as a guide but, when he and the folk in his workshop saw it on the chopper, it’d clearly found its true home. I was planning a metal-flake paint job originally, but the alloy just fits in as it is. My mate Ron gave it a good polish and I really love it as it is now.

Ian at Marshall Speed & Custom supplied a lot of the bits and bobs; cables, hoses, dogbone risers, chain conversion, etc. He’s been my supplier for this sort of stuff for many years now, and knows what’s what with Harleys. My mates helped me too, with various one-off parts, advice, abusive comments, and cups of coffee.

The donor bike already had a set of repro springers, and I got Central Wheel Components to lace up a 21-inch front wheel. I put the whole shebang back together, and sent it over to Dave at Iron Wire in Resolven to be wired up. He did an outstanding job of breathing life into the old girl, creating a loom from scratch and (with cries of “It lives! It lives!”) he handed it over to Celtic Cycles to get it roadworthy and MoT’d, as they’re good at dotting the Is and crossing the Ts where I tend to paint with a big brush.

I’m pretty stoked that she rides so well, although riding around the wrecked roadways of a disused RAF base for the photographs nearly wrecked my back ( that’s part of the retro vibe… man). I feel she embodies both the style and the spirit of the 1960s scene as shown in the Irvin Penn photographs from California in the 1960s, and the bikes in the Roger Corman film Wild Angels. People seem to get it – people whose opinion I respect, and that’s cool because when you’re alone in the shed with a load of Harley parts and an idea, you can have doubts. This time it all worked out just how I’d pictured it and that’s certainly a good feeling – a good feeling like viewing the road through a pair of apehangers, and everybody needs that, don’t they?