As we begin a new year – and a new decade – sit back and savour the wise and witty words of the late Jim Fogg RIP.

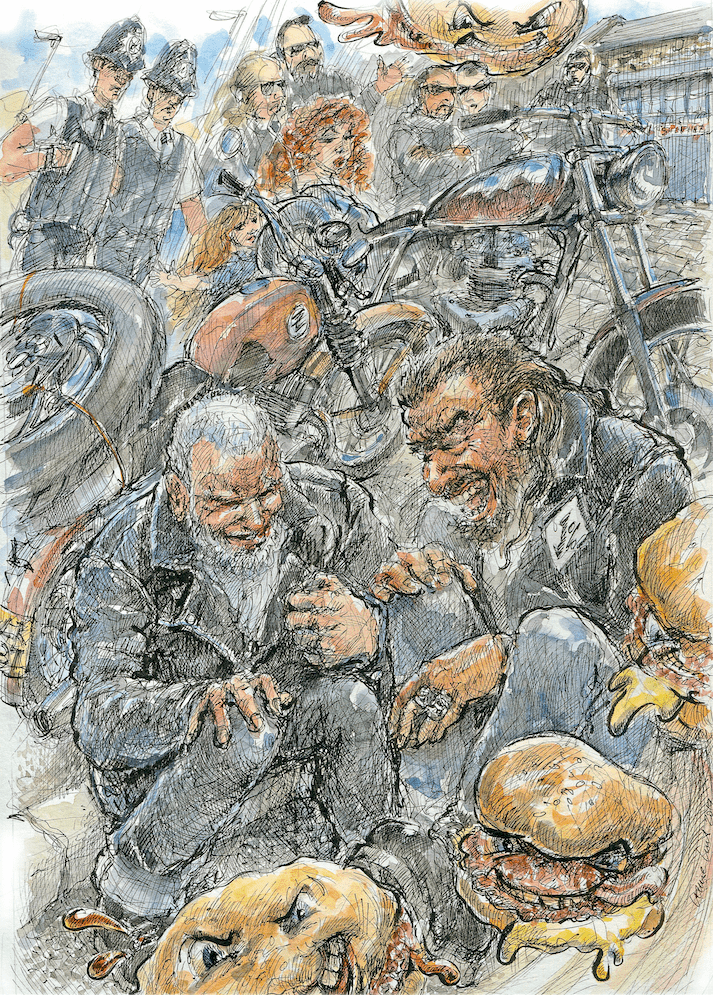

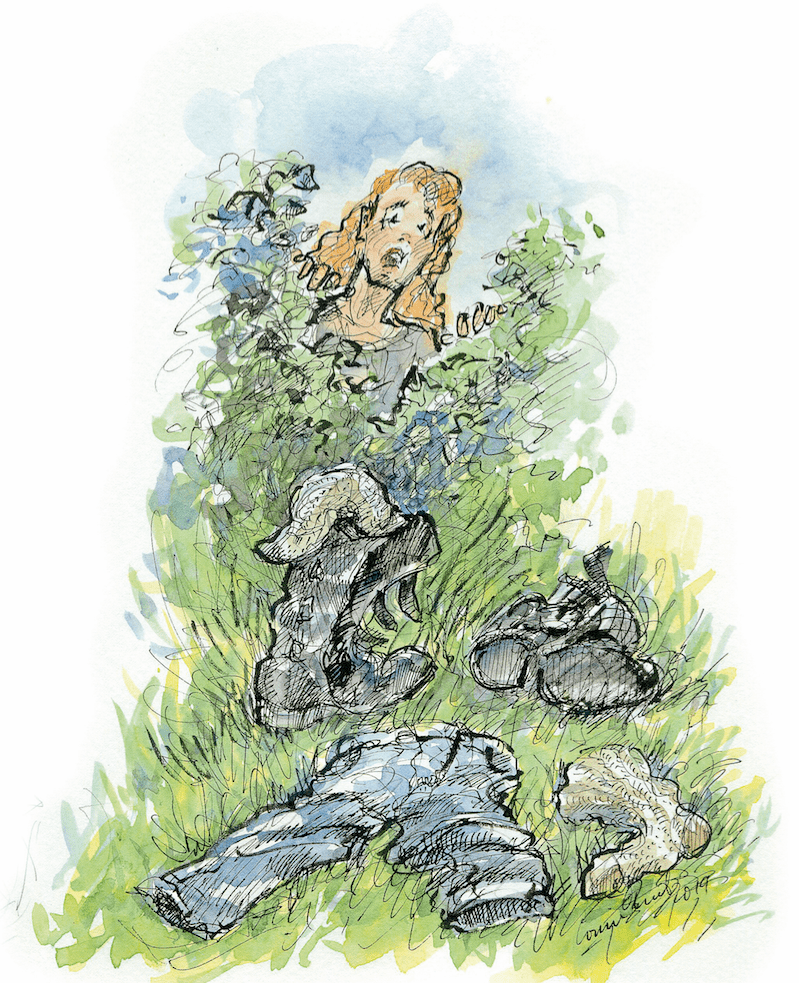

Illustrations: Louise Limb

Maybe I was wrong to blame the beefburger, but thinking back it was sure as hell glistening ominously as the girl stuck it between two halves of a bun. The onions looked a bit metallic too, like the last oil to drain out of a gearbox, and the relish resembled a slow hedgehog in repose for eternity on a night-time road. Whatever caused it, I had two-and-a-half unpleasant days to think about it… when I wasn’t praying for death and calling up God on the Great White Telephone.

Enjoy more Back Street Heros reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

I don’t understand why I’m always ill on my days off from work, but that weekend was the ultimate bummer. I ran over a bottle with the XV750 as I was riding into my backyard, and just had enough time to watch the front tyre deflate before nature called pretty urgently. I dropped the bike on to its prop-stand, and disappeared up the stairs for the next three hours, gritting my teeth hard, and doing a rapid quick-step out of my Levi’s, wondering which end was going to blow first…

When I came down, the Yam’d toppled over off its stand, and had fallen on to my 350 Jawa. Jawas being what they are, there wasn’t a mark on the Czech superbike, but it’d nearly written off the goddam XV750.

Maybe I ought to explain about the Jawa? Well, it seemed a snip at £50, and I thought I could do with something to ride around on when I send my V-twin off to Crazy ’Odge for a piece of mild customising this winter. Nothing excessive, you understand; just removal of the air filters and a bit of re-jetting to let those two 40mm carbs breathe a little better before the hot air blasts out of the turnouts, a nice rawhide seat, oh, and purple metal-flake paintwork with gold scrolling. Maybe a bit of engraving, brass-plating, maybe a nice mural on the tank… you know how these ideas tend to grow until they’ve used up all your money. Be that as it may, like I said the Jawa seemed a good idea, even if it was a rusty two-stroke with no class, and the ability to cover everything in a fine mist of superheated oil. In fact, it reminded me of one of my first bikes, a Villiers-engined Excelsior, which isn’t too surprising considering Jawa used the same engines as a lot of British firms pre-war. All the firms who used to use them in this country had the good sense to go bankrupt, though…

Actually, the Jawa is a dog, but it’s a reliable dog, even if the footrests keep unscrewing themselves, it doesn’t have a choke to aid easy starting, and you have to travel everywhere with a gallon of two-stroke oil, and a kidney-donor card, just to be prepared for any eventuality. I threw away the Barum tyres and fitted a pair of Korean Swallow tyres, and they don’t seem bad… although I still have doubts about a product designed to keep you on the road which proudly advertises on the sidewalls “100% Nylon, No Natural Rubber Used”. This might be taking ecology too far, maybe even at the expense of humanity. None of this worried me that particular weekend though, I was too busy puking and crapping… quite often at the self-same time too.

The first day I was wondering whether I’d got campylobacter, salmonella, or any one of a few novelties produced by bacillus coli, which is harmless in the colon but not too good anywhere else. The second day, when I realised that I couldn’t even phone for the doctor because I’d lost my voice through all that puking, was when the odd spell of panic set in… or it would’ve done if I hadn’t been spending most of the time lying on the bathroom floor moaning hoarsely. By that time, I wasn’t too bothered about anything at all, although it crossed my mind that I’d’ve traded both bikes for a bottle of the famous Indian Brandee or the odd litre of kaolin-and-morphine (not that they tend to sell anything that makes you feel good in chemists’ these days… and that includes a lot of interesting cough medicines, too).

By that time I was feeling pretty hungry, but I hadn’t been able to do any shopping, so all I had in the house was All-Bran, and lots of tins of baked beans, which I thought I’d better try.

You don’t really want me to tell you what happened then, huh?

Monday morning, after a trip to the local bakery for a granary loaf, which went down quite well with a quarter bottle of Scotch I’d been keeping for such emergencies as toothache, snake-bite, and visits by relatives, I was feeling a whole lot better, so I decided to answer the insistent knocking on my front door, and give the world a personal appearance.

It was a dishevelled middle-aged lady of distinctly Romany aspect, and she thrust a large bundle of white heather into my face. They caught in my beard, and it hurt like hell when she pulled them out.

“Lucky white heather,” she croaked. “Lucky white heather… don’t forget it’s bad luck to turn a gypsy away from your door, sir.”

My usual answer to that is “Don’t you know it’s bad luck to be booted down a path by a biker?”, but I noticed that her left hand and arm were heavily bandaged, so I didn’t say anything, motivated by lack of voice as much as by charity I’ve got to admit.

“How much?” I croaked back in return.

“’Ere, you taking the piss?” she answered hoarsely, in much the same voice. “It’s bad luck to…”

“… take the piss out of gypsies,” I finished. “Just give me the bloody heather, huh?”

“All of it?” she asked, and I nodded wearily, and crossed her palm with cupro-nickel.

As she was leaving, wishing me a long life, many children, and success in all I did, I asked her about the bandages.

“How did you hurt your arm?” I asked.

“Got bit by a badger,” she told me, “while I was picking lucky white heather…”

That cheered me up a lot.

Well, just think about lucky rabbits’ feet, too – if they were that lucky they’d still be attached to the rabbit’s legs, and not dangling from key-rings.

I went into the backyard and, a couple of days later than I’d intended, picked the Yam up from where it was lying obscenely across the Jawa. The front tyre was still flat (even lucky white heather has its limitations, obviously) and, not only that, but I noticed that the tread-pattern was getting a little thin, so I thought I might as well get a new Dunlop while I was in the process of taking the wheel to Frank’s, so I set about removing it, once I’d got the bike back on the centre-stand.

Everyone knows how easy it is to get a front wheel out these days, because the manual tells you how easy it is. Manuals never seem to mention, though, how the split-pin in the wheel spindle nut breaks off, with one broken half sliding up your thumb-nail, then when you pull it out you notice how rusty it was, and how much blood there is. Then the nut itself has obviously been tightened on by King Kong’s big brother, and you end up standing on an eight-pound adjustable wrench to try and loosen it off, until finally you take up a three-pound lump hammer and beat the wrench until the bastard finally begins to move. Not to mention that the wheel spindle itself takes the application of the same hammer to a large steel spike to start to move it sideways and out of the fork eyes. That’s when the wheel falls out, but you can’t lift it free because there’s not enough clearance between it and the mudguard because you should’ve put the bike up on blocks before you started, but you’ve forgotten. I’d reached that stage when there was a rattling burble down the back-alley, and an acquaintance rode up to show me his latest purchase.

“Thought you’d like it,” Carrots told me brightly. “Well, you’re into Yams, aren’t you?”

“Not at this effing moment,” I assured him, and straightened up wearily, sweat dripping into my eyes. “Why’d you get rid of the LC?”

When I tell you that Carrots is a gangly teenager with red hair, who wears the biking wimp’s uniform of full-face motocross helmet, 38-buckle steel-splined scrambler’s boots, and a cut-off with a Newcastle Brown bar-towel sewn on it, you’ll know why I was expecting his next remark.

“Dropped it,” he told me, with a look of bemused pride. “And then it wouldn’t run right afterwards.”

It’s my opinion that two-strokes were never designed to run right in the first place, but LCs maybe run better than most… until everything wears out that is, which happens periodically, by which I mean about once a month.

I looked at the XS250. It was red, some of it, and a slimy black, oily colour where the engine should be. The seat was covered in a mosaic of carpet-tape, the front mudguard had the worst case of Jap Pucker I’d ever seen around the rivets, and was starting to bend upwards as the chrome and steel rotted, and there were an awful lot of wires sticking out doing nothing much in particular.

“It’s a four-stroke,” he assured me. “It sounds like a real bike…” I was beginning to start to like Carrots, and then he blew it. “…just like me mate’s Superdream,” he finished. “What’s up, Foggy? You’re looking a bit strange.”

“I haven’t been well,” I told him, and the noxious exhaust-fumes from his arrival were beginning to make my guts rumble worse than a Triumph with a seizing main-bearing. “I’ve had the runs, and I haven’t eaten much for a good few days.”

He produced a parcel from the front of his cut-offs. “Have some of this,” he offered, and unwrapped a greasy pizza that looked like a set of melted-down traffic lights. “It’s green and red peppers, and there’s a slice of black pudding on top… bloody ’ell, Foggy, you’ve gone a funny colour. Err, I was wondering if you could rewire me bike for me?”

I nodded, it didn’t seem wise to open my teeth at that particular time, and he rode away, scattering nuts, bolts and something that might’ve been third gear all along the alley.

I finally heaved the Yam’s front wheel free, and wearily began to rope it to the top-box on the Jawa.

“My, that’s a good idea,” a cheery voice said. “A spare wheel’s always handy, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Vicar,” I replied, taking the line of least resistance, and not feeling up to explaining the disparity between Yamaha’s swirl-cast alloy wheels, and Jawa’s skinny spoked jobs.

“I’m just down here visiting Mrs Wilson,” the vicar told me, which wasn’t too informative since nearly everyone along the row is called Wilson except me. “She’s had a rather nasty tummy bug, and I always think you need cheering up after something like that, don’t you?”

“No,” I croaked. “What you need is leaving bloody alone.”

The vicar smiled nervously, probably aware of all the heavy ironmongery lying around in my backyard, ready to hand, and noticing the strange expression starting to spread over my sweaty face. He bade me good day, and I grunted in reply.

The Jawa started up fifth kick and, once it’d warmed up, and the blue vapour’d cleared, I set off. If you’re not too well, it’s hard to remember that a Jawa gearbox works the other way round to a Jap’s, but the first couple of bends bring a certain clarity of mind – especially when you think you’re accelerating out of them, the revs hit the three million mark, and it feels as if you’ve just ridden into the surf at Malibu, and you realise that first gear is where you thought third was.

When I got to the local bike shop, the place was full of German and French bikers, and they were all buying tyres in a multilingual babble that left old Frank there entirely unmoved. It was complete chaos until he decided he’d had enough. He held up his arms, and the babble died away to a mutter.

“Sort yourselves out,” he told them, and then caught sight of me. “How are you doing, eh? What’s the problem?”

“Can I have another of these, Frank?” I asked him. “Oh, and a new tube, and some rim-tape, too?”

“’Course you can,” he said amiably. “Get the lad to look one out for you.”

An irate-looking German biker stepped forward, and posed Frank a question. “Vhy,” he growled, “are you dealing with this people first, vhen ve haf been here already for many minutes?”

I wasn’t inclined to argue, since the German lad topped me by about five inches, looked as if he had muscles in his spit, and was surrounded by six equally frustrated big blond companions.

“Because,” Frank told him, enunciating clearly. “I know him, and I don’t know you. All right?”

A certain stony silence settled on the gathering, so I thought I’d better do my best to foster European relations. Unfortunately, my mind’d gone a complete blank (this isn’t all that uncommon, even when I’m not suffering from the after-effects of bacteria) so the first thing I said was, “Err, pity about the back brakes seizing on the new BMWs, isn’t it? Not to mention the problem with the fuel-injection?”

A French guy sniggering from somewhere in the middle of a cloud of smouldering Gauloises, brought to mind that humour was what drew peoples of all nations together, although I can’t explain why I then said, to the assemblage of French and Germans: “’Course, you know why all the avenues in France are lined with trees?”

There were blank looks from everyone.

“Well,” I told them brightly, “it’s so the Germany Army always has somewhere to march in the shade when they invade.”

Everyone laughed at that when it first appeared in the pages of The Sun, but no one seemed to find it very funny in Frank’s bike shop that day, which obviously proves to me that you shouldn’t try to tell jokes when you’ve been ill.

I was saved from whatever fate was going to befall me by the arrival of the lad, who handed over the wheel with a new Dunlop, still with its rubber whiskers in place. I signed the cheque, and left the shop with around 14 pairs of foreign eyes drilling malevolently into my back.

In the car park, while I was roping the wheel to the Jawa, I was just in time to witness the arrival of a newly built lowrider, with its owner, one of the local outlaws whose name I didn’t know, and’d never bothered to solicit, aboard it. It’s an interesting point, but I’ve become aware recently that more people know me than I know. This might be the price of fame, in which case I can live with it. Mr Myatt assures me that I’m well on the way to becoming a cult figure – apparently, he was told this when he was down at the last Kent Show, when somebody said: “’Ere, that Fogg’s a real cult, isn’t he, huh?’ Well, I think that’s what the guy said, anyway…

“How’s it going, you geriatric old bastard?” the owner of the lowrider asked me, as I grunted back and peered at his bike.

I don’t know why I was surprised, as the French do it all the time, which is what you’d expect the way they ride bikes, but I was taken aback to see a set of Jap forks and a cast wheel in a British hardtail frame – they didn’t go at all well with the spoked 5.00×16 rear tyre, but then not everyone’s a purist like me. What did look okay, enough for me to think about getting ’Odgie to fit one on the Yam, was the neat little CX500 Custom tank nestling on the frame top tube – it seemed to go very well with the black-barrelled pre-unit BSA motor.

I looked up at the owner. Under all the grime and stubble his face looked a distinctly odd shade, a bit like putty when the linseed oil in it has gone rancid, a bilious greenish-grey.

“Okay,” I told him, “and I like the bike. You okay, though? You’re not looking too good?”

“Bloody burgers,” he answered, and I knew exactly what he meant. He got off the saddle wearily, and put the bike on its prop-stand. “Or it might have been the prune punkaluna,” he added morosely. I might give you all the recipe for prune punkaluna someday, if I can ever remember it… or if I want to, because fermented prunes aren’t something you’d want to drink a lot of, and I don’t really hate anybody that much, but it’s my experience that if you’re poor enough there isn’t a thing you won’t try to ferment.

“It’ll be the burgers,” I reassured him, “punkaluna only eats the lining of your…”

I got no further. The BSA hurled itself off the prop-stand, and toppled sideways in majestic slow motion, right on top of the Jawa, which crunched into the tarmac under it. This time, Czech engineering and British iron being what they are, neither bike was much damaged. Laughing like a couple of deranged dingoes, the outlaw and I dragged up the BSA, righted it, and then did the same to the Jawa.

“Thank Christ your bike isn’t bent,” I told him, “and the Jawa seems pretty undamaged, too.”

He looked at the vast expanse of rust, dirt, oil and paint the colour of lead primer, and at the cracking seat and Honda topbox, and the different makes of footrest rubbers, grips and indicators, and a smile started to cross his tired and grey face.

“Jesus, Foggy,” he cracked out, “how can you bloody tell?”

The sight of two bikers sitting on the tarmac laughing like maniacs didn’t unnerve too many people, although it was noticeable that no one got too close either.

“What are they doing, Mummy?” a little girl asked her hippy-style mother, as they both ambled past in long dresses, orange blouses, and plaited headbands. The hippy lady, not a bad-looker with her long brunette hair and scrubbed-clean face, gave us a quick look, and decided some reassurance was necessary for her offspring.

“They’re meditating, Dawnlight,” she said, “just like Daddy and I and the rest of us grown-ups do.”

“But why are they laughing?” the little girl piped up. “They’re not serious.” Quite right, you can always rely on a kid for incisiveness, which is more than we got from a red-faced gent with a bristling white military moustache, who hustled his matronly wife past with some speed.

“…drugs, no wonder the country’s in a mess,” I caught him saying, “just like those people in Malaya…”

“I think it was Borneo, dear,” his wife put in.

“…natives, anyway,” he continued, “high as a kite, then they’d run amok, chopping people up with meat-cleavers. You’ll see, it’ll be in the papers tomorrow.”

A passing policeman, walking along in blue shirtsleeves, watched us closely for a minute or two, and then walked over.

“Now then,” he started to say, and then recognised me. “Bloody Nora’, he continued, “I thought you were dead!”

“I nearly have been,” I told him, and explained the weekend’s events, aided by graphic descriptions of the BSA owner’s similar malady.

The world is full of comedians. “Mind how you go,” the copper said. “Oh, and mind where you go, too. Evening, all.” It was 3.30 in the afternoon.

We got to our feet, wobbled over to the bikes, and started them up – it seemed wise to get on our ways before the patrol cars arrived.

“Fancy a brew?” I asked the outlaw, from out of the centre of a cloud of blue fumes. He nodded, and we set off back through town. I was in front, then all of a sudden there was a roar alongside from his BSA, and he shot past, shouting something I could only just catch the tail-end of…

“… real bad,” I heard him say. “Gotta get to one fast…” From which it seemed likely that his gastric problems were taking a new turn for the worse, so I followed him fairly rapidly until we came to a public convenience. Like a Pony Express rider changing horses, he leapt from the saddle, kicked the prop-stand down with the bike still ticking over, and ran towards the green-painted building. When I caught him up, it was just in time to see a look of acute pain cross his already-grim face. I read the typed notice on the door, barred and padlocked like the entrance to Fort Knox, over his shoulder. It read: ‘These conveniences have been closed for the season owing to vandalism, and for maintenance. Your nearest conveniences are at Marine Road Central (Promenade), Morecambe.’ Five miles away.

“Try the Ladies,” I said. “Round the other side, I’ll bet they haven’t been vandalised or closed.”

When he emerged, fortunately without being disturbed by any female intrusion, he was actually grinning. “Hey, you wanna see the graffiti in there,” he told me. “There’s a good one about how you’ve got a real small…”

“Just get on your goddam bike,” I said.

He fired the BSA up, and he was laughing so much he was shaking even more than guys on BSAs normally do. We set off back to my place via the scenic route, along quiet country lanes leading up hill and down dale, smelling the wild garlic and honeysuckle as we went, and hearing the bird-calls and the insistent buzzing of bees. For the first time in a day or two I began to feel pretty good, which proves what sun and warmth, and the absence of misplaced peristalsis, can do, and how the richness of life and its quality can be enhanced by something so simple as not having to sit on top of the load of porcelain holding a bucket.

We rode round a bend between two drystone walls, almost home, and I suddenly saw a bike lying on its side in a gateway, engine ticking over, chain still driving the back wheel. There was a lot of noise, a lot of dust, and it looked pretty bad when I saw the helmet lying close to the bike. The outlaw and I stopped, cut our engines, and got off to look for any trace of a body. The bike looked familiar; it was a ratty-looking 250 Yamaha, and I was trying to remember where I’d seen a red XS250 when I spotted the tangle of untidy wiring.

“Christ, it’s somebody I know,” I said to the Beesa owner. “He must’ve taken a dive over the wall when he came off the bike.”

“He’s not going to be too good, then,” he answered. “It’s about 15 feet into the field.”

We walked slowly over to the gateway, and looked over the gate into the field. No sign of anyone.

“Maybe someone’s already picked him up,” the outlaw said. “Yeah, he’s probably in hospital by now. You’d’ve thought they’d’ve taken the bloody trouble to move his bike, though.” I nodded, and then my eyes caught something further along the field, on the way to a clump of stunted bushes, almost at the far end. It was a bike boot, steel-shod, and with many buckles. Once I saw that, I began to make out other items of clothing discarded in a hurry; a sock, another boot with the sock still in it, and a pair of Levi’s. A carroty head emerged from the bushes, looked round, saw us, disappeared, and then emerged again.

“Err, hi there, Foggy,” Carrots shouted weakly across at me. “Err, have you got… err, any paper?”

“Give him this,” the outlaw said, and handed me an official-looking typed document. It was a form from the Social Security telling the BSA owner that the findings of the tribunal were that he had been dismissed from his employment for a legitimate reason (namely, striking his employer), and therefore he would not be entitled to benefit for six weeks.

“Seems reasonable,” I told him. “For the purpose Carrots intends for it, I mean.”

Carrots emerged about 15 minutes later after we’d handed him his clothes; and he proved once again that the resilience of the young is a truly sickening virtue. “Fancy a pizza?” he asked us brightly, as he walked back to his bike, now silent and restored to stability on its centrestand. “Go on, I’ll treat you both. A pizza apiece, a malted choc-o-milk, and some battered sausages, how’s that sound, huh? All that crapping don’t half make you hungry.”

I looked at the outlaw, and he looked at me. “No-one’d ever find him,” I said.

“Not if we dug him in deep enough,” the owner of the BSA lowrider assured me. “And we could drop his bike on top of him, too.”

“Not a trace,” I answered. “No-one’d know.”

“Hey, come on, you two,” Carrots squeaked, backing away with a look of considerable disquiet on his spotty face. “I was only joking, Foggy, there’s no need for the two of you to get uptight.”

“Do you want your wiring doing?” I asked him, and he assured me that this was so, and that he would be grateful if I could.

“Don’t ever, and I mean ever, mention food while I’m around,” I explained to him. “Food is a taboo subject, a dirty word, never to be discussed in front of me. Okay?”

“Well, okay,” he said. “You old blokes don’t half get touchy about some odd things, it must be your hormones.” And young people wonder why other people take mole-grips, torque-wrenches and small planks to them, huh?

I relented, and said to Carrots: “Get on your bike, and follow us. I’ll get the wheel back in my own Yam, and then we’ll try and sort out the wiring on yours…” which we did, the outlaw and me between us. Later we all sat in the backyard drinking beer while the sun went slowly down, and all our bikes blocked up the back alley to access by all those Toyotas, Marinas and mopeds. It wasn’t a bad end to a fairly eventful day, and the Beesa owner and I were talking quite a bit about old times, while Carrots listened in, probably wondering why we didn’t mention Jap bikes all that much, and what the hell a Rocket Three or an Interceptor was.

“It must’ve been great in the old days,” he said, quite a bit of the cheek in him mellowed by gratitude and beer. “I’ll bet you could tell a few tales about some of the runs you had, huh?”

I grinned, feeling pretty mellow myself. “I think I might just write something about this weekend’s first,” I answered, and Carrots looked blankly at me.

“But you haven’t been anywhere,” he said.

“There are runs and runs,” the BSA lowrider owner put in, and smiled a little more easily than he’d been doing earlier. “It’s a goddam pun, Carrots, a play on words.”

“Like a joke?” the red-haired young biker asked. “Like ‘runs’ meaning going off on bikes and ‘runs’ meaning you’ve got to go and spend a lot of time sat on the…”

“You’ve got it,” the outlaw told him.

Carrots grinned too. “No, I haven’t,” he answered a little muzzily. “But I thought I had, sitting back there in that clump of bushes.”

It suddenly occurred to me that the future of biking wasn’t entirely lost as long as there were promising young-punks like Carrots around, and I started laughing all over again.

“How old are you, Carrots?” I asked him.

“Eighteen,” he answered, looking puzzled.

I took another drink from the can of beer. “When I was your age, I was 18,” I told him.

“I don’t understand that,” he replied, looking even more puzzled.

“You will when you’re an old bastard like both of us,” the outlaw assured him, and I reckon he’s probably right, too, because that’s the way it goes.