To the uninitiated, even the latest model in the development of Harley-Davidson’s air-cooled powerplant looks like it could’ve been built at any point within the last 70 years or so, given the basic, unchanging design of the 45-degree vee twin.

Words: Dave Manning

Pics: Simon Everett

Enjoy more Back Street Heros reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Unless you’re enough of an anorak to be able to immediately distinguish between Panheads and Shovelheads, Ironhead Sportsters and Evo’ Sportsters, Evolutions and TwinCams and Milwaukee 8s (although, to be fair, most of us are!), then all of the different iterations of the overhead valve Harley twin are, visually, pretty much the same.

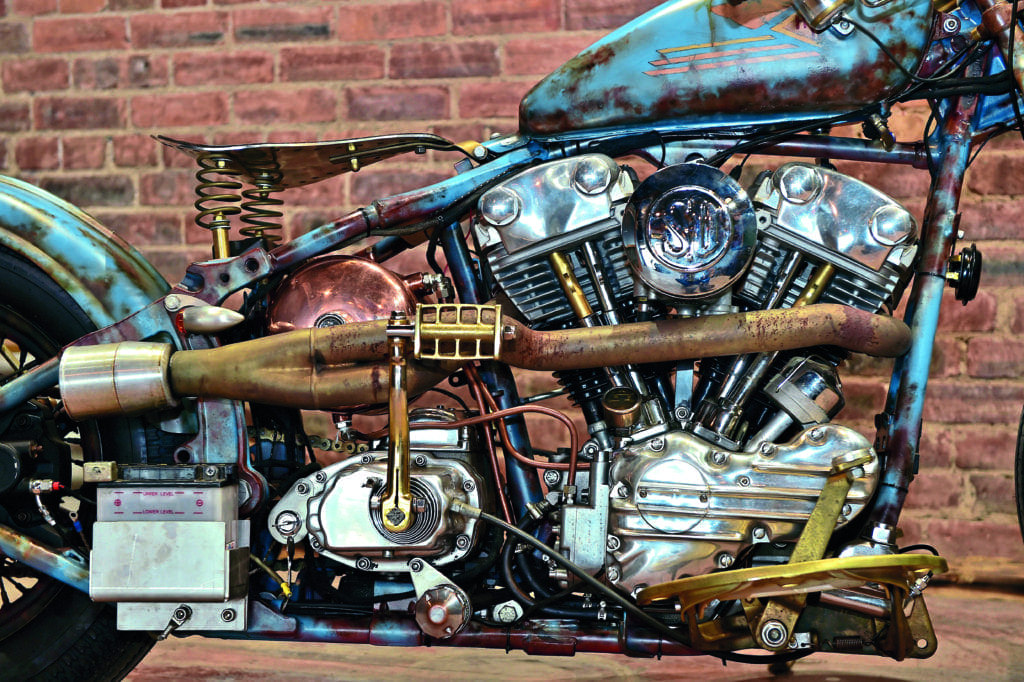

And, once you think you’ve got it sussed with regards to the architecture of the different generations of engines, along comes someone with what, initially, appears to be a classic Milwaukee Knucklehead, assembled at some point between 1936 and ’47. However, take a closer look at Lukasz Wierbicki’s bike, and you’ll swiftly realise that this isn’t a classic bike from the Forties, but actually a much more modern Harley, with rear suspension, that’s powered by an S&S Super Stock engine (which is an Evolution-style motor) fitted with Knucklehead-style cam cover and rocker boxes made by Xzotic Cycle in the US.

Originally machined in Dallas, the tooling for the covers was bought by Custom Chrome International who now supply the parts, and the Xzotic covers actually fit over the standard covers, rather than replace them, with the result that the cam cover looks a bit more true to form than the rocker covers, which don’t quite fully disguise the Evo heads. Nonetheless, they’ll confuse a few folk, and they certainly give a more vintage look to the Evo engine. The older look is helped by the fact that the gearbox is a five-speed kicker, unlike the standard Evo transmission which is, of course, electric start only, and having a kickstart lever makes onlookers automatically assume that a bike is a ‘proper’ classic.

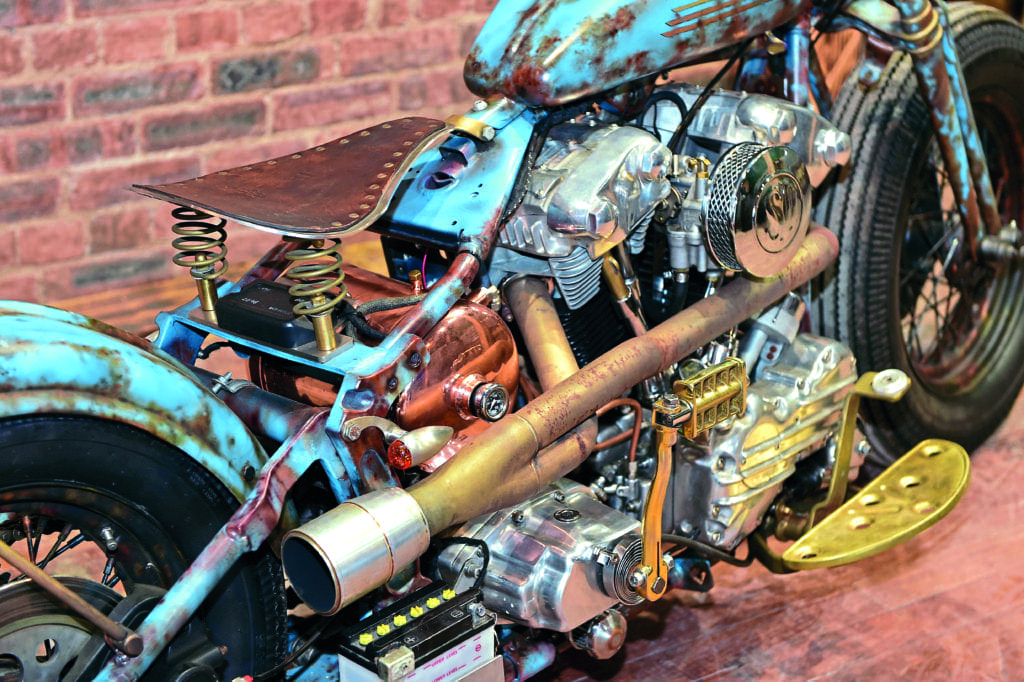

This bike was actually first built in Germany, as a hardtail, having already won several trophies before Lukasz got hold of it. Wanting to make it his own bike, he was always going to make a few changes, and they certainly weren’t minor, as he started by changing the frame for a Harley Softail in order to get a little more comfort – the intention was that it was going to get used on the road, regularly, and he wanted to be able to clock up the miles without recourse to a chiropractor or physiotherapist.

He didn’t do all of the work himself; no, he did it in conjunction with a bunch of guys from a shop in Poland called RHC. Lukasz is Polish, you see, although he lives and works in the UK (he’s a professional driver in the North East). They used a near-standard Softail frame, while the front end comprises a fork set from Zodiac, styled like the springer forks that would’ve been fitted to a Knuckle, although it has mounts for a torque arm for the twin piston hydraulic caliper as the 16-inch wheel is fitted with a brake disc rather than a drum. The chunky wheel and correspondingly fat Shinko tyre are matched at the rear, with a further disc and twin-pot caliper hauling the plot to a halt. Given the low-down punch of the 1340cc S&S engine, this is probably far wiser than opting for stylistically appropriate drum brakes…

A fuel tank and rear mudguard of unknown origin are fitted such that the upper profile of the bike flows smoothly from the top of the headlight through to the rear wheel, with the mudguard bolted to brass struts on the swinging arm rather than the frame to keep clearance to an aesthetically pleasing minimum. Much like the hardtail that was originally used, in fact!

To keep the top yoke clear of clutter, the speedometer is mounted on the right-hand side of the fuel tank, while rather neat brass switches from Kustom Tech are used on the swooping handlebars. Further parts from the Kustom Tech catalogue are used in the form of a brake master-cylinder and clutch perch, both using brass levers. More brass was used in the construction of the forward controls and the footboards, while further use of the material after it’d had the zinc removed (i.e., basic copper) can be seen in the oil tank and the rigid pipes that supply and return the oil from and to the tank. The copper and brass elements do give something of a Victorian engineering feel – some might call it steampunk, but there’s not enough of a science fiction aspect for that, and that’s vital if anything is going to have that particular label attached.

The oil tank was made by RHC, who were also responsible for the ‘patina’ style paintwork on the bike, incorporating not only the bodywork, but also the frame, forks and wheel rims. Aside from the rust effect used on the ferrous parts, the illusion of age is also increased by the use of the old-style Harley logo on the tank and, indeed, the very colour that is used as a base – a baby blue that alludes more to the Twenties and Thirties than any kind of deep, rich and heavily lacquered paint used more recently.

While Lukasz is more than happy with the end result, having owned it for more than two years now, he’s itching to build another (more radical) bike, so this one is for sale. Interested parties can get in touch via BSH Towers.